- Unknown girl, from pile of discarded photos in Woodruff, Wisconsin antique store.

In an antique store in Woodruff, Wisconsin, I came across a little album of autographs. It had a well-worn velvet cover, and its contents told me that it was the property of Emelia Daw (nee Buchert), who received it in 1890 at the age of 15 years. The last signature is in 1930, when Mrs. Daw (as she is addressed in the later salutations) would have been 55 years old… the same age I am now.

All of the signers wrote “Dear Emelia (or Mrs. Daw)”, followed by a formulaic inscription. Her “friend and teacher”, Marguerite Hill, wrote:

“Premeditate your speeches, words once flown

Are in the hearer’s power and not your own.”

On May 19th, 1898, Otto Brandt wrote, with creative spelling: “Dear Emilie, If you love me as I love you know knife can cut our love in to.”

The pages are signed “Your Friend”, “Your brother”, “From Your Dear Melda” (her daughter, who signed twice). The earliest signers wrote in German, so I can’t vouch for the contents, but I think it’s safe to assume they followed the convention of the day and wrote well-used tropes. One of my favorite pages is from Emilia’s sister, who wrote in 1897:

“Sister Emelia,

The time is swiftly passing by,

When we must bid adieu,

We know not when we meet again,

So these lines I leave with you.”

In the corner margin, she wrote: “Remember the pantry jokes”. Salt in the sugar bowl? What mischief did they cook up?!

I brought the album to the Chicago Botanic Garden, where I am teaching a class in calligraphy. My students were fascinated with the beauty of the penmanship. The writers used quill-shaped pens dipped in ink bottles, similar to the ones we use in class. As the years went along, the writing became less formal, resembling Palmer cursive hand-writing. One imagines that the manner of dress and speech also became less formal, as these German immigrants adjusted to their life in America and things became more modern. Today, we can compose and publish with no pen, no paper, and no pants on.

They had names like Alma, Anna, Elsie, Hermann, Otto, Hazel. They came from Wisconsin towns called Bancroft, Ellington, Hortonville, Greenville, Washburn, Appleton, Watertown and Stevens Point. I think Emelia came from Hortonville, which made me laugh, because Hortonville was always my family’s synonym for “Nowhere” after our car broke down there on a family road-trip.

Emelia cherished this little album for at least 40 years. As her friends married, she went back to their autograph page and inscribed it with their wedding date (e.g., Henry Riesenweber, Ellington, March 11, 1891; married 13 Oct., 1901.)

Each of the inscriptions, with its ornate calligraphy or pencilled scrawl, conjure up a personality. One can almost hear their voices. As a person who embraces the fluidity and ease of technology, I find that calligraphy brings a slow pace and tactile quality to writing that is all but lost today. In the careful forming of letters, the scratch of pen on paper, the setting-up of ink between two scored lines from a metal pen, the content of the inscription (whether it be a saccharin couplet in an autograph book or a literary quotation) becomes a separate concern. For Emelia’s friends, their inscription showed their devotion; writing was their gift.

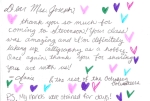

I am learning Copperplate, a very formal and difficult style of calligraphy. Here is my practice piece:

It humbles me that Marguerite Hill, Emelia’s “friend and teacher”, wrote better than I do, and she wrote that way ALL THE TIME.

It humbles me that Marguerite Hill, Emelia’s “friend and teacher”, wrote better than I do, and she wrote that way ALL THE TIME.